NIGERIAN

NURSES AND MIDWIVES UNEMPLOYMENT SURVEY

University

Graduates of Nursing Science Association (UGONSA)

gnan2ugonsa@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Background:

The

quacking controversy that trailed the Nursing & Midwifery Council of

Nigeria’s (N&MCN) release of a “License Community Nurse (LCN)” circular (Ref

No. N&MCN/SG/RO/CIR/24/VOL.4/152 dated March 3, 2020) which conveyed the

intention of the council to lower the existing standard of nursing education for

the LCN programme that will take secondary school leavers at least a credit in

English and Biology to be admitted into and two years to complete, and inter alia blamed the crude situation

and abysmal performance of the Nigerian Primary Healthcare (PHC) system in the

community settings on mass migration of Nurses & Midwives to urban areas

and to other countries prompted UGONSA to initiate this survey to empirically

determine whether there are indeed a shortage of Nurses & Midwives to fill

the manpower need of the Nigerian PHC system in the community settings or not,

or whether the shortage is as a result of the deliberate age-long policy of attrition

and displacement of Nurses & Midwives from the PHC system in the community

settings and their replacement with Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) [who

do not have nursing education, training, skills or the ethical leaning to be

responsible and accountable for nursing & midwifery services] by the National

Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA).

Objective:

The

main aim of the study was to determine if there is a shortage of nurses that

could fill the nursing needs of the PHC system in the community settings. The

study also sought to compile the list of unemployed and underemployed Nurses

& Midwives and to find out if unemployed Nurses & Midwives are willing to

work in the community settings if the opportunity to serve the PHC system in

the community setting is offered to them by the NPHCDA. The study further sought

to determine the ratio of unemployed Nurses & Midwives in relation to the possible

number of graduates that can be licensed by the N&MCN in a session.

Methods:

Using Google forms an

online compilation was carried out from

March 7 to April 08, 2020, in a descriptive survey of unemployed Nurses &

Midwives that could be reached online within the timeline. Names, Phone

numbers, State of Residence, Year of Graduation, Qualification(s), and how long

they have remained unemployed after graduation were compiled. In addition, two

questions were asked about the objective of the study. Analysis of data was

done via Google forms statistical tools.

Results:

A total of 3317 unemployed Nurses & Midwives responded to the

survey. Among these unemployed

Nurses & Midwives – 38% holds RN only, 19% holds both RN & RM, 15.4%

holds RM only, while 27.6% holds BNSc plus another qualification. For the year

they have remained unemployed after graduation 57.1% have spent 0–2 years,

29.9% have been unemployed for 3–5 years, 7% have been unemployed for 6 – 8 years

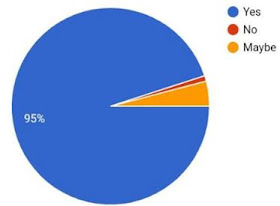

and 6.1% have been unemployed for more than 8 years. To the question, “Do you think there is a shortage of Nurses

and Midwives in Nigeria?” – 47.5% said yes, 43.5% said no whereas 9% were undecided

(said maybe). Furthermore, the result showed that while 95% of the unemployed Nurses

& Midwives are willing to work in the rural community settings, 1% was not willing

to work in the rural community settings and 4% were undecided (.i.e. said maybe)

on whether they will work in the rural community settings or not. The result

also revealed that the 3317 unemployed Nurses

& Midwives captured in the survey represents graduates of 66 Nursing

& Midwifery schools per session out of a total of 162 schools that are

currently accredited by the N&MCN. This represents 41% of the possible number

of graduates that can be turned out of the accredited Nursing & Midwifery

Schools (excluding Post-basic schools) in a session.

Conclusion:

Despite

the reported migration of Nurses to urban areas and other countries, at least 41%

of Nigerian Nurses & Midwives produced in a session remain unemployed and

95% of them are willing to work in the rural community settings if given the

opportunity. These unemployed Nurses & Midwives can bridge the Nursing

& Midwifery manpower needs in the Primary Healthcare System should the

NPHCDA engage their services with a commensurate or higher payment to what

their employed counterparts receive in Federal Government-owned establishments

and hospitals. There is no current shortage of Nurses that necessitates the lowering

of the existing standard of nursing education. Nurses & Midwives are not

responsible for the design, implementation, and delivery of healthcare services

at the PHC level and therefore are not culpable for the deplorable condition

and abysmal performance of the Nigerian PHC System.

Recommendations:

1 1. NPHCDA

should create a department of nursing & midwifery services to oversee and

handle issues of nursing & midwifery services rather than outsourcing nursing

& midwifery services to the CHEWs as it has perennially done and currently

does.

2 2. NPHCDA should start recruiting Nurses

& Midwives to carryout nursing & midwifery services for which they were

educated, trained, and licensed rather than outsourcing these services to the

CHEWs.

3 3. The NPHCDA should spend a greater part

of its yearly budgetary allocation on upgrading the Primary Healthcare

facilities to at least the minimally acceptable global standard.

4 4. Nurses & Midwives working in the

rural community settings in the PHC system should receive an equal or higher

remuneration than their counterparts working in Federal Government-owned

establishments and hospitals.

5 5. State Governments should start recruiting and deploying to the rural community settings in their respective States at least 100 (one hundred) Registered Nurses and Midwives, including those with Bachelor of Nursing Science (BNSc) degree, every year to boost the availability of skilled nursing workforce in the rural areas.

6.The Nursing & Midwifery Council of Nigeria (N&MCN) should engage the NPHCDC to create a Department of Nursing Services for Nurses & Midwives and to start employing them to render nursing & midwifery services for the PHC system in the community settings.

6.The Nursing & Midwifery Council of Nigeria (N&MCN) should engage the NPHCDC to create a Department of Nursing Services for Nurses & Midwives and to start employing them to render nursing & midwifery services for the PHC system in the community settings.

6 7. The N&MCN should retract the

circular (Ref No. N&MCN/SG/RO/CIR/24/VOL.4/152 dated March 3, 2020) that

erroneously blamed the failure of the PHC system to make the desired impact in

the Nigerian health system on the migration of Nigerian Nurses to urban areas

and other countries rather than on the real cause which is the deliberate perennial

war of attrition on Nurses & Midwives by the NPHCDA that has ended up ostracizing

them from the system and replacing them with the CHEWs.

7 8. The

N&MCN should create clinical licensure for Nurse Practitioners in the Community

Health Nursing specialty at MSc & Ph.D. levels that will equip and empower post-baccalaureate

prepared Community Health Nurses to independently diagnose and treat common

ailments suffered in the communities and coordinate the care of patients in the

community settings as done by Nurse Practitioners in developed climes such as

the United States and Canada.

8 9. UGONSA should engage with and submit the

compiled list of the unemployed Nurses & Midwives to the Federal Ministry

of Health (FMOH), the National Assembly, the National Association of Nigerian

Nurses & Midwives (NANNM) and the N&MCN for robust and comprehensive engagement

of all stakeholders and the NPHCDA to absorb the unemployed Nurses &

Midwives in the PHC system to work in the community settings in line with the

extant schemes of service for Nurses & Midwives and pay them similar or

higher salaries and allowances payable to Nurses & Midwives in Federal

Government-owned hospitals and establishments.

This article should be cited

as follow:

{University

Graduates of Nursing Science Association [UGONSA]. (2020). Nigerian Nurses and

Midwives Unemployment Survey. Position paper/Survey Diary 3}.

Limitations:

1 1. The

findings were based on the fact that the N&MCN grants 50 slots to each

school per session and thus the possible number of graduands per session being

when each school presents 50 candidates for the council exams and all the

candidates presented passed the exams (100% pass rate). This rate was adopted

in order not to overestimate the unemployment rate of nurses and midwives in

relation to the number of nursing & midwifery schools.

2 2. The number compiled and computed was the

number of unemployed Nurses & Midwives that willingly responded online to

the survey within a month (March 7 to April 8, 2020). Those that were not

online during this period and even those that were online but chose not to

respond to the survey were unaccounted for. Therefore the figures contained in

the findings of this study may be far less than the actual number of unemployed

Nurses & Midwives in Nigeria at the time of the survey.

Keywords: Unemployment, Nursing, Midwifery, opportunity, remuneration,

facilities.

Background:

The

Nursing & Midwifery Council of Nigeria stirred a quaking controversy in the

Nursing community when on March 3, 2020, it released a circular Ref No:

N&MCN/SG/RO/CIR/24/VOL.4/152 which conveyed its intent to lower the

existing standard of nursing education via the introduction of a 2-years program

for a lower cadre of Nurses christened “Licensed Community Nurse (LCN)” with

having a poor O’level result (.i.e. at least a credit in English and Biology) being

the principal admission requirement. The circular titled, “ INTRODUCTION OF

COMMUNITY NURSING PROGRAMME AS A MODALITIES FOR STRENGTHENING NURSING HUMAN

RESOURCES AT THE PRIMARY HEALTHCARE LEVEL AND REDUCTION OF MATERNAL AND INFANT

MORTALITY IN NIGERIA” sounded that currently there is a great demand for

nursing care to be assessable to children, adolescents, adults, older people,

vulnerable groups, victims of crime and disasters, and internally displaced

persons, in their communities and settlements [which indeed is the primary

reason for the existence of the Primary Healthcare (PHC) system]. The council

in the circular attributed its reason for embarking on the voyage of breeding

this lower cadre of nurses to “gross

shortage of Nursing manpower at the community level occasioned by the mass

migration of Nurses to urban areas and other countries with a resultant

weakening of the Primary Health System and poor access to healthcare by rural

dwellers in the country”. The

council went further to cast the health-related Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs) and Universal Health Coverage (UHC) as unmet in the country owing to

shortage of Nurses to paddle the boat of care in the rural community settings hence

the need to lower the existing standard of nursing education and create the

lower LCN cadre to fill the gap (N&MCN, 2020a). Put in another way, the

N&MCN acknowledged that the Primary Healthcare system of Nigeria is in a

total mess but that Nurses should be blamed for this mess for their migration

to urban areas and other countries.

While

many nurses and nursing groups agreed with the council that the Primary

Healthcare (PHC) system is in a degrading rot they vehemently disagreed that

the appalling state of the system was caused by a shortage of nursing manpower to

drive the system and cautioned the council not to jeopardize the existing

standard of nursing education or the quality of nursing manpower with the

planned lower cadre nursing program which prospectively targets the weakest

secondary school graduates (.i.e. those with at least a credit in English and

Biology) for admission into nursing (N&MCN, 2020a). Many believed that

there is no shortage of nursing manpower in Nigeria citing the mammoth crowd of

nurses that apply for recruitment whenever any government-owned hospital floats

advert for recruitment of nurses as the basis for their stand. They argued that

if similar payment for the nursing & midwifery job opportunities availed

for Nurses & Midwives in Federal Government-owned hospitals or

establishments that do attract a mammoth crowd of unemployed Nurses &

Midwives, whenever job adverts are made in Federal Government-owned hospitals

or establishments, should also be made available at the rural community

settings via the Primary Healthcare (PHC) system, many Nurses & Midwives

would troupe into the communities for employment.

In the opinion of many nurses, the National

Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA) was rather to be blamed for

failing to engage the services of the many unemployed Nurses & Midwives who

are roaming the streets in search of scarce nursing & midwifery jobs. Nursing

is the heartbeat and cornerstone of the PHC system globally but in Nigeria, the

NPHCDA has since its creation in the year 1992 removed nursing as the

cornerstone and rather made the outsourcing of nursing & midwifery services

to the Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) its driving policy. The CHEWs

were created as a smokescreen for waging an organized war of attrition on

Nurses & Midwives in the PHC system by the medical doctors who hold sway at

the Federal Ministry of Health right from the inception of the NPHCDA principally

to dislodge nursing from holding any position of influence in the system that

may attract respect for the profession from the rural community dwellers and the

general public. In bowing to pressure from his medical colleagues to create the

CHEWs as a tool to wither the influence and contribution of Nurses &

Midwives in the health system, Prof. Olikoye Ransome-Kuti (the Minister of

Health under whose tenure the NPHCDA was established in the year 1992) had

falsely alleged that Nurses & Midwives had rejected taking up nursing &

midwifery services in the rural community settings even when nobody had

mobilized them for such in the then newly established PHC services and thus he

sinisterly created the CHEWs as a replacement for Nurses & Midwives in the

PHC system using this false allegation as a red herring. Professor Ransome-Kuti

had regretted this action when he left office after seeing the health indices

of the country worsen as a result of this faulty policy he had promoted in the

health system. As he admitted when he stood down as the Minister of Health, "my only regret as I leave the ministry

is that I have not been able to mobilize all health workers behind the medical

system. Most health workers are only interested in how to maintain their

position in the hospital system." (Raufu, 2003). Thus, Prof.

Ransome-Kuti, like other Ministers of Health (MOH) who are medical doctors,

have had the golden opportunity of mobilizing all the health workers behind the

Nigerian health system but chose to be divisive & chauvinistic and more

interested in assigning and maintaining positions for their medical colleagues.

The parsimonious regret and acknowledgment of Prof. Ransome-Kuti that he had deliberately

ostracized and replaced Nurses & Midwives with the CHEWs instead of

mobilizing them behind the health system because he chose to appease his

medical colleagues who are more interested in occupying and being in charge of positions

over deploying skilled nursing & midwifery services in delivering

qualitative healthcare to the people in the rural community settings was rather

playing to the gallery as nothing has been done till date to correct the

anomaly.

Nigeria

thus sadly represents an anomalous situation where the central coordinating roles

of nursing have been ceded to the CHEWs at the detriment of quality client care.

This has made the health indices of the country negatively nosedive and has catapulted

the country’s health system to an exalted seat among the global worse health

systems despite having a PHC system that has engulfed millions of dollars over

the years. NPHCDA has over the years relegated Nurses &

Midwives to the background and egregiously made the CHEWs the cornerstone of

nursing & midwifery services of the PHC system in the rural community

settings despite that the CHEWs do not have nursing education, training, skills

or the ethical leaning to be responsible and accountable for nursing &

midwifery services. The situation is so bizarre that the CHEWs are made to even

assume leadership over nursing in a few situations where Nurses & Midwives

are allowed access to the system that has been deliberately gated against them.

In other words, the CHEWs are in charge of and administer nursing &

midwifery services in the Nigerian PHC system despite not being qualified

Nurses & Midwives or having the competency and the capacity to do so and

they are bizarrely in charge of nursing & midwifery services in the rural

community settings even when qualified, capable and competent Nurses &

Midwives are available.

The

deliberate displacement of Nurses & Midwives from their jobs with the CHEWs

is glaringly evident in the NPHCDA dedicating one out of its nine departments

to the services of the CHEWs (.i.e. the Department of Community Health

Services) whereas no department of Nursing services exist at the agency to

coordinate and oversee nursing & midwifery services as is the norm in

climes where nursing is playing its normal central coordinating roles in the

PHC system. Nursing which ordinarily should be the bedrock, backbone, heartbeat

and the cornerstone of the system is alas the rejected central pillar in the

Nigerian PHC system.

Nursing

is nowhere near the system design or leadership of the PHC, which are mainly occupied

by physicians, few administrators, and the CHEWs to the exclusion of Nurses

& Midwives, despite that the core of the services rendered by the system is

nursing & midwifery services. Not having a department of Nursing Services at

the NPHCDA portends that nurses have no frontline roles in the PHC system of

the country and therefore are not responsible for the mess in the system. This

is especially as the model of healthcare services delivered in the community settings

under the PHC system in Nigeria is CHEW-driven, CHEW-centred, and, CHEW-headed

rather than nursing driven, nursing-centered, or nursing-headed. To dish out

CHEW services in place of nursing & midwifery services and expect to get

the results for nursing & midwifery services is foolhardy. To blame nursing

for the failure of the PHC system whose nursing & midwifery services are handled

by the CHEWs (who have no nursing & midwifery background or preparation) at

the expense of Registered Nurses &

Midwives is preposterous. The case of the PHC system in ceding nursing &

midwifery services to the CHEWs in the rural community settings is akin to ceding

engineering works to carpenters and still expecting to get a good result. The

Nigerian PHC system is arguably in a total mess because people that do not have

nursing & midwifery background were mobilized and made the centrifuge for

nursing & midwifery services over the years. Therefore, the failure of the

PHC system should be squarely blamed on the NPHCDA for making the system more

of an obtuse political system that is interested in maintaining positions, as

confessed by Prof. Ransome-Kuti, than a healthcare delivery system that

mobilizes appropriate personnel for qualitative care delivery. Until the square

peg is put in the square hole the PHC system of Nigeria will remain a sham.

A

review of the contemporary health indices of the country especially those of

the rural community settings which the NPHCDA was established to turn around

are imperative in the subject matter. The National Primary Healthcare

Development Agency (NPHCDA) was established in the year 1992 with a mandate to

make healthcare delivery in the community settings robust to achieve universal

health coverage for Nigerians and stem the tide of high maternal and child mortality

& morbidity in Nigeria. However, the worsening contemporary health indices of

the country show that the agency is very far from achieving this mandate and

needs an urgent systemic rejig and a comprehensive overhaul. Nigeria has consistently

remained among the most dangerous place for a woman to be pregnant or a child

to be born in the world courtesy of failure of the PHC system to address the health

needs of the rural communities (Odetola, 2015; Odogwu, 2018). Ononokpono and

Odimegwu (2014) lamented that although there has been a decline in maternal

deaths globally, the maternal mortality rate in Nigeria is still unacceptably

high as pregnancy & delivery is still very well associated with suffering,

morbidity, and death especially in rural community settings. In Nigeria, it has

been reported that an estimated 2,300 children under the age of five and 145

women of childbearing age die every single day, making the country to account

for the second-largest number of maternal and child deaths in the world (United

Nations Children’s Emergency Fund [UNICEF], 2015; Ifijeh, 2016). CIA World

Factbook (2018) equally reported that the maternal mortality rate resulting

from obstetrics episodes in Nigeria is estimated to be 814 deaths/100,000 live

births, which is about four times higher than the global average of 216 deaths

per 100,000 live births (WHO, 2018), making Nigeria that accounts for 2.4% of the

global population to carry 14% of the global burden of maternal mortality

(USAID, 2016). The high maternal & child mortality rate in

the community settings has been attributed to inadequate utilization of skilled

manpower to provide maternal & child healthcare services (Ononokpono

and Odimegwu, 2014). Delivery in a health facility, staffed with skilled

healthcare providers such as Nurses & Midwives is associated with lower

maternal & child mortality and morbidity rates compared with delivery at

centers that lack skilled Nursing & Midwifery services (Odetola, 2015; Ifijeh,

2016; WHO, 2018). The National Primary Health Care Development Agency (Nigeria)

[NPHCDA] itself in its report confirmed that the Nigerian Primary Healthcare

(PHC) system grossly lacks the services of skilled care providers such as

Nurses & Midwives and attributed such to be responsible for the high

incidence of maternal & child mortality and morbidity witnessed in the country.

NPHCDA (2016) had reported that of 61% of pregnant women receiving care by a

skilled provider in Nigeria, only 38% of births are attended to by skilled

birth providers while only 36% deliver in health facilities with skilled

providers, which mostly are located in urban settings. This report by the NPHCDA

itself shows that it knows that its age-long practice of relegating skilled

nursing & midwifery services to the background with the CHEW services in

the rural community settings is the bane of the PHC system but elected to

continue to perpetuate such on the chancel of politics. The poor state the PHC

system has been heralded into over the years was even corroborated by an earlier

report from the 2008 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) which stated

that only 38% of pregnant Nigerian women deliver in a health facility with

skilled providers which are mostly located in the urban areas (National

Population Commission, ICF Macro, 2009). WHO (2011) capped it with its report that

Nigeria has had a very poor record regarding maternal and child health outcomes

as an estimated 53,000 women and 250,000 newborns die annually mostly as a

result of preventable causes. This figure is even worsening as the years go by

(Odogwu, 2018). There has been an air of suspicion among Nurses that the

Midwifery Service Scheme (MSS) established in the year 2009 for the deployment

of qualified, unemployed or retired midwives, to selected primary health care

facilities in rural communities to facilitate an increase in the coverage of

Skilled Birth Providers (SBP) to reduce maternal, newborn and child mortality was

allowed by the NPHCDA to die off out of lack of funding because some highly placed

individuals in the agency were at odd as per why the scheme should engage the

services of midwives and not that of the CHEWs. The introduction of the now-defunct

MSS would not have even arisen or been necessary in the first place had Nurses

& Midwives been engaged and deployed for the services of the PHC system in

the rural community settings over the years.

At the present moment, the woes of those in

the community setting are further compounded by different factors that fuelled

the surge of internally displaced persons (IDPs) within the past decade such as

terrorism, herdsman crisis, communal clashes, and natural disasters. Having a

litany of IDPs camps in the face of non-functional PHC system with crude

facilities dotted with CHEWs’ services supplanting the much needed skilled

nursing & midwifery services portend that children, women, adolescents,

adults, older people, vulnerable groups, victims of crime and disasters, and

internally displaced persons have been abandoned to their fate in the community

settings.

From

the foregoing, it is convenient to infer that the Sustainable Development Goal

(SDG) 3, which borders on good health and well-being, will perpetually remain a

mirage in Nigeria rural communities as long as the status quo of relegating

skilled nursing & midwifery services to the background persists in our PHC

system. Since the N&MCN blamed

the failure of the PHC system on the shortage of nurses and on the other hand, many

Nurses and nursing groups denounced and disagreed with this claim by the

council and rather blamed the mess on the NPHCDA for supplanting nursing &

midwifery services with CHEW services, it is thus imperative to determine empirically

whether there is indeed a shortage of nurses or not and whether unemployed

nurses & midwives are willing to work in the rural community setting should

the opportunity be offered to them.

Methods:

A compilation of unemployed Nurses & Midwives was done online via various social

media platforms of the Nigerian nursing community using Google forms. Data

collection was done from March 7 to

April 08, 2020, compiling unemployed Nurses & Midwives that could be

reached online within the timeline. The descriptive survey sought to have a

compiled list of unemployed Nurses & Midwives at the time of the study and

as well elicit their responses on the notion of a shortage of nurses and their

willingness to work in the rural community setting if offered the opportunity. The

following socio-demographic data were collected: Names, Phone numbers, State of

Residence, Year of Graduation, Qualification(s), and how long they have

remained unemployed after graduation. In addition, two questions were asked in

line with the objective of the study with options for selecting “Yes, No or

Maybe”. The two questions are: (1) Do you think there is a shortage of Nurses

and Midwives in Nigeria? (2) With a good remuneration, good working condition

and good facilities, will you be willing to work in the rural community

setting? Data collected were analyzed using Google forms’ statistical tools.

Results:

A total of 3317 unemployed Nurses &

Midwives responded to the survey. Among

these unemployed Nurses & Midwives – 38% holds RN only, 19% holds both RN

& RM, 15.4% holds RM only, while 27.6% holds BNSc plus another

qualification. For the year they have remained unemployed after graduation

57.1% have spent 0 – 2 years, 29.9% have been unemployed for 3–5 years, 7% have been unemployed for 6 – 8 years and

6.1% have been unemployed for more than 8 years. To the question, “Do you think there is a shortage of Nurses

and Midwives in Nigeria?” – 47.5% said yes, 43.5% said no whereas 9% were

undecided (said maybe). Furthermore, the result showed that while 95% of the

unemployed Nurses & Midwives are willing to work in the rural community

settings, 1% was not willing to work in the rural community setting and 4% were

undecided (.i.e. said maybe) on whether they will work in the rural community

setting or not. The result also revealed that the 3317 unemployed Nurses & Midwives captured in the survey

represents graduates of 66 Nursing & Midwifery schools per session out of a

total of 162 schools that are currently accredited by the N&MCN as stated

on the council website [.i.e. 85 Schools of Nursing, 42 Schools of Basic

Midwifery, 27 Departments of Nursing and 8 schools of Community Midwifery

program] (N&MCN, 2020b). This was derived from the fact that the Nursing

& Midwifery Council of Nigeria (N&MCN) allots 50 indexing slots per

school per session. This infers that the existing schools have the potential to

graduate 8100 Nurses & Midwives per session should they all present 50

candidates each for council exams with all the candidates passing the exams. Therefore

the unemployed Nurses & Midwives represents at least 41% of all graduates

expected to be turned out by all the Nursing & Midwifery Schools combined (excluding

Post-basic schools) in a session assuming that all the schools index and

present 50 candidates each for the Nursing & Midwifery qualifying exams and

that all candidates presented for the exams pass them.

How long have you been unemployed?

Do

you think there is a shortage of Nurses & Midwives in Nigeria?

With

good remuneration, good working condition, and facilities will you be willing

to work in the rural community setting?

Qualifications

Discussion: The

findings that 7% of the unemployed Nurses & Midwives have been unemployed

for 6 – 8 years and that 6.1% have been unemployed for more than 8 years is

striking for a country whose PHC system was said to be having a gross shortage

of nursing manpower. The results showed that available Nurses & Midwives are

in excess and unemployed for many years after graduation and not in shortage as

stated by the N&MCN. The finding that many Nurses & Midwives who are

willing to work in the rural community settings remain unemployed for even up

to more than 6 to 8 years after graduation strongly disagreed with the position

of the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria in the circular, (Ref No.

N&MCN/SG/RO/CIR/24/VOL.4/152 dated March 3, 2020), wherein it posited that the

quest to fill in the gap of ‘a great shortage of nursing manpower’ to be

engaged for delivery of care in the rural community settings had necessitated its

move to lower the existing standard of nursing education to produce a lower

cadre of Nurses in the form of Licensed Community Nurses (LCN) who would be

admitted into nursing for a two-year program with a poor O'level result of at

least a credit in English and Biology. The study showed that there is no

Nurses’ shortage gap for the N&MCN to fill with the proposed LCN since a

good number of the available Registered Nurses & Midwives are still unemployed

years after graduation. Again, the findings that among the unemployed Nurses

& Midwives are nurses with dual or multiple qualifications indicates that

these unemployed Nurses & Midwives have specialized skills to bring on

board in the community settings to improve health and well-being of the rural

dwellers should their services be engaged by the NPHCDA to serve the PHC system

in the community settings.

The findings that 95% of the unemployed Nurses

& Midwives are willing to work in the rural community settings if offered

the opportunity confirms that it was not a shortage of nurses that buoys their

little or none visibility at the rural community settings but not being offered

the opportunity to work in the PHC system at the community settings by the

NPHCDA. Not finding any opportunity at the community level they switch to any

available option such as self-employment, abandoning nursing for other businesses

or vocations and turning to urban areas or other countries for employment

opportunities. The study, therefore, contradicts the postulation of the N&MCN

that the inability of the people in the rural community setting to assess the

much-needed nursing services is due to the shortage of nurses occasioned by the

mass migration of nurses to urban areas and other countries.

The findings that at least 41% of the possible

numbers of Nurses & Midwives that can be licensed by the N&MCN in a

session are unemployed shows that unemployment is a serious issue among

Nigerian Nurses & Midwives. This unemployed leftover from the annual

turnover of Nurses & Midwives in Nigeria can bridge the nursing manpower needs

in the rural community settings if engaged and deployed to serve the system from

year to year. From the study, it is now comprehensive that while other

countries make deliberate effort to build up their nursing manpower at the

grassroots and ensure universal health coverage across communities by adopting

extreme staffing measures for skilled healthcare providers such as engaging the

services of foreign nurses, in Nigeria, the reverse is the case. The Nigerian

Primary Healthcare (PHC) system has perennially adopted an uncouth extreme

measure of ostracizing Nurses & Midwives from the system such that the skilled

nursing manpower that is supposed to cover the rural communities remain

unengaged as nursing & midwifery services are egregiously ceded to the

CHEWs who are not prepared educationally, ethically, or professionally to render

nursing & midwifery services or be accountable for such. Thus, unemployed

Nurses & Midwives that have been dislodged from the PHC system where they are

supposed to serve and help improve the health indices of the country readily fall

into the prying eyes of exploitative private hospitals in urban areas and the

health system of other countries that are looking for nursing manpower to make

up their deficits. Despite migration to the urban area and other countries, at

least 41% of Nigerian Nurses & Midwives produced in a session still roam

about without a job.

Conclusion:

Giving

the opportunity 95% of unemployed Nurses & Midwives are willing to work in rural

community settings. At least 41% of the possible numbers of Nurses &

Midwives that can be licensed by the N&MCN in a session are unemployed. The

unemployed nurses can bridge the nursing & midwifery manpower needs in the

Primary Healthcare (PHC) system should the NPHCDA engage their services with

commensurate or higher payment to what their employed counterparts receive in the

Federal Government-owned hospitals and establishments. It was erroneous for the

N&MCN to blame the crass failure of the Nigeria PHC system to meet its

mandate to the Nigerian people on the shortage of Nurses & Midwives or

their migration to urban areas or other countries. There is no current shortage

of Nurses that necessitates the lowering of the existing standard of nursing

education. Despite the said migration of Nurses to urban areas and other

countries, at least 41% of Nurses & Midwives produced in a session remain

unemployed and 95% of them are willing to work in rural community settings. Nurses & Midwives are not responsible for

the design, implementation, and delivery of healthcare services at the PHC

level in the community settings and therefore are not culpable for the

deplorable condition and abysmal performance of the Nigerian PHC System.

References

Abimbola, S., Okoli, U., Olubajo, O., Abdullahi, M.J., & Pate, M.A.

(2012). The Midwives Service Scheme in Nigeria. PLoS Med, 9(5): e1001211

CIA World Factbook. (2018). Nigeria Maternal Mortality Rate. Index

Mundi. Retrieved 26/03/20 from http://www.indexmundi.com/nigeria/maternal_mortality_rate.html.

Global Health Workforce Alliance. (2017). Nigeria Midwives Service Scheme. Retrieved online 06/04/2020

from https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/forum/2011/hrhawardscs26/en/

Ifijeh, M. (2016). Reducing

Maternal, Child Mortality in Nigeria. Thisday March 24.

National

Population Commission, ICF Macro (2009). Nigeria

Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Abuja, Nigeria: National Population

Commission and ICF Macro.2009. Google Scholar.

Nursing

& Midwifery Council of Nigeria [N&MCN]. (2020a). Introduction of

Community Nursing Programme as a Modalities for Strengthening Nursing Human

Resources at the Primary Healthcare Level and Reduction of Maternal and Infant

Mortality in Nigeria. Circular Ref No:

N&MCN/SG/RO/CIR/24/VOL.4/152, dated March 3.

Nursing

& Midwifery Council of Nigeria [N&MCN]. (2020b). Approved Schools.

Available online, http://nmcn.gov.ng/apschool.html.

Retrieved 26/3/2020.

Odetola,

T.D. (2015). Health care utilization among rural women of child-bearing age: a

Nigerian experience. The Pan African

Medical Journal. 2015;20:151. doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.151.5845.

Odogwu, G. (2018). Assessing SDGs

implementation in Nigeria. Punch Newspaper. Available: https://punchng.com/assessing-sdgs-implementation-in-nigeria/

Okeke, E.N., and Setodji, C.M. (2018). About the Nigerian Midwives

Service Scheme (MSS). RAND Center for

Causal Inference. Available online https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral policy/projects/born/mss.html

Ononokpono,

D.N., and Odimegwu, C.O. (2014). Determinants of maternal health care

utilization in Nigeria: a multilevel approach. The Pan African Medical Journal,

17, (Supp 1):2. doi:10.11604/pamj.supp.2014.17.1.3596.

Raufu,

A. (2003). Olikoye Ransome-Kuti. British

Medical Journal (BMJ), 326,(7403): 1400.

UNICEF (2015). Nigeria Maternal and

Child mortality in 2015. Geneva. UNICEF global databases 2015, based on

MICS, DHS, and other nationally representative sources. Retrieved 27/03/20 http://data.unicef.org/.

United Nations Population Fund

[UNFPA]. 2014. Setting standards for emergency

obstetric and newborn care. Retrieved 08/04/20 from http://www.unfpa.org/resources/setting-standards-emergency-obstetric-and-newborn-care.

No comments:

Post a Comment